WHY WE SHOULD RESPECT THE NECK OF THE HORSE!

By Karin Leibbrandt DVM

Also published in Issue 7 of the CONCORIDA INTERNATIONAL EQUESTRIAN MAGAZINE – the current issue and archived issues are free to read and download.

As a veterinarian specialising in rehabilitation, I’ve been working with horses on a full-time basis for 20 years now. When I started rehabbing horses I had a variety of patients. Some had kissing spines, some were recovering from tendon injuries, and occasionally I came upon horses with neck injuries like synovitis or osteoarthritis in the 6th and 7th vertebrae of the neck (C6-C7) or pinched nerves. But recently, 100 percent of the rehabilitation horses under my guidance have one or more neck injuries.

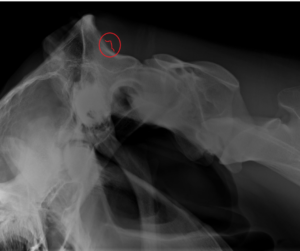

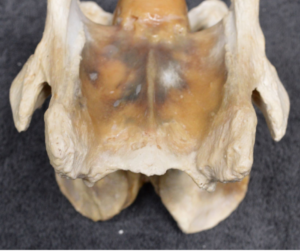

Most neck injuries can be found in C6-C7, sometimes they also occur in C5-C6-C7. Sporadically, horses show issues in C2-C3 and new bone formation at the nuchal crest (crista nuchae) which is the point where the nuchal ligament attaches to the skull.

Picture 1 – above: In the red circle the nuchal crest with new bone formation.

What happened? Why is the neck so vulnerable?

Over the past 50 years (and longer), there have been some dramatic changes in the breeding goals leading to the present-day sport horse. We focussed on true athletes, with elegant bodies and tiny heads, tall bodies, long-lines and with long legs. Increased flexibility of the joints produces extravagant gaits and spectacular lateral movements.

But there is a downside to all of this – increased flexibility turned into hypermobility.

Hypermobility is defined as an increased range of motion of joints. Of course, this contributes to suppleness, but too much suppleness makes the horse unstable in his entire body and especially in the lower neck. So why the lower neck in particular?

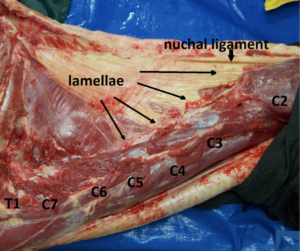

There are a number of contributing factors. As recent research has shown, most modern domestic horses, including sport horses, don’t have all nuchal ligament lamellae, they miss the lamellae of C6 and C7.

Picture 2 – above (Equine Studies) shows a sport horse, missing the lamellae on cervical vertebrae C6 and C7. This causes an instability in the neck. There is no upward support by the lamellae in the lower neck.

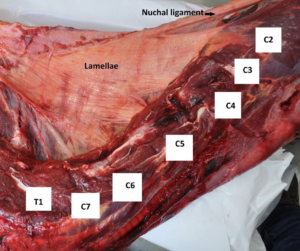

Picture 3 – above (Equine Studies) shows a zebra. All nuchal ligament lamellae are present and all cervical vertebrae, C2 to C7, are being stabilised.

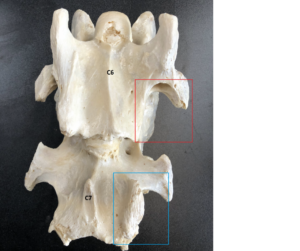

Another factor contributing to increased instability is a condition called Equine Complex Vertebral Malformation (ECVM). Not every horse shows this problem, but it is a common finding. In this case, there is a malformation of the caudal ventral tubercle (CVT) at C6. Sometimes this deformity is unilateral, sometimes bilateral. In some cases, a part of the tuberculum of C6 is missing, and sometimes we find a transposition of this part to C7.

These malformations cause instability as well as asymmetry in the neck. Certain deep muscles of the neck attach to the CVT, so if the CVT is missing or if there is a transposition to C7, the deep muscles have no attachment points at all, or they are attached in an asymmetrical way. As might be expected, this has consequences for the biomechanics of the horse.

Picture 4 – above (Equine Studies) shows ECVM. Part of the tubercle of C6 (red square) can be found on C7 (blue square).

Picture 5 – above (Equine Studies) shows a normal C6

Another factor is the focus on breeding elegant athletes, during which the balance of the horse changed.

Picture 6 – above: We can see that the withers are higher compared to the hindquarters. However, looking at the sternum we can see that the sternum has lowered, it went forward and downward, and the first part of the back has dropped. The spinal processes of the vertebrae of the withers got longer, but the bodies of the vertebrae lowered. If we drew a line through the patella and the elbow, we could see the line sloping downward.

Picture 7 (above): The angles of the front leg got smaller and the angles of the hind legs got bigger. This makes the hind legs relatively longer and the front legs relatively shorter, causing the point of gravity to shift to the front.

The horse needs to brace the first thoracal part of the back and the caudal part of the neck to compensate for the weight on the forehand. And, because the horse lowers the first part of the thoracic spine and lower neck, the angle in the lower neck gets smaller, causing more tension in this area.

The impact of Rollkur/hyperflexion/LDR (low, deep and round)

If horses are being trained short in the neck or even LDR, the lower neck lowers even more including the first part of the back. This means the horse needs to brace this part of his body even more and the angle between C6, C7 and T1 is getting smaller. This causes a lot of tension in the facet joints and the intervertebral discs. Another aspect is the increased tension on the attachment of the nuchal ligament on the skull and the hyperflexion in C2-C3.

If the horse is trained in a low deep and round position with a lot of force, the impact on the lower neck is even bigger.

Although the modern sport horse has the predisposition to develop lower neck problems, training short in the neck is one of the leading causes for lower neck issues. This is why the knowledge about hypermobility, missing lamellae, ECVM and unbalanced conformation is very important. We should train horses in a way that helps them find their balance and helps them to lift the lower neck as well as the first part of the back, so that they can stabilise this part of their body, relax and feel comfortable.

Instead of training for suppleness, we should train for stability. Keep the movements in the neck small – with no overbending to the left and right or hyperflexion – since all of these increase the risk of neck injuries.

In conclusion, we should treat the neck of the horse with respect, since especially in modern sport horses, the neck is extremely vulnerable.

Special thanks to:

Zefanja Vermeulen from Equine Studies. Zefanja always supports my work by providing educational photos.

Karel de Lange for sharing his information about the balanced and unbalanced conformation of the horse.

Glossary

Neck vertebrae: Also called cervical vertebrae. Just as humans, horses have seven cervical vertebrae (C1 through C7), with C1 being the first vertebrae next to the skull and C7 the last cervical vertebra, next to its first thoracic counterpart called T1.

Nuchal ligament: The large ligament connecting the dorsal spinous processes of the vertebrae. It starts at the skull, runs along the top of the horse’s neck, over the withers and then connects to the lumbar vertebrae. It consists of a fanned out part in the neck (the lamellar portion) and a rope-like part in the back (the funicular portion).

The nuchal ligament plays a critical role in supporting the head and neck of the horse, as well as the horse’s and rider’s weight when standing and in movement.

Nuchal ligament lamellae: Fanned-out portion of the nuchal ligament. This part was thought to attach to all cervical vertebrae (C2-C7). However, newer research has shown that in domestic horses, lamellar attachments only occur to C2-C5 and not to C6 and C7 (few exceptions reported).

Nuchal crest (crista nuchae): Bony crest at the top of the skull where the nuchal ligament attaches. Not to be confused with a ‘cresty neck’, which is also called nuchal crest, but refers to fat deposits along the crest of the neck in horses and ponies (nuchal crest adiposity) which have been associated with equine metabolic syndrome.

Caudal ventral tubercle (CVT): In general, certain protrusions located at the spinous processes of a vertebra. Tubercles are anchor points for muscles. At C6 and C7, this would primarily be M. Longus Colli, a muscle that helps to stabilise the neck. These attachment sites are missing in horses with ECVM.

WHY WE SHOULD RESPECT THE NECK OF THE HORSE! By Karin Leibbrandt DVM is published in Issue 7 of the CONCORIDA INTERNATIONAL EQUESTRIAN MAGAZINE – the current issue and archived issues are free to read and download.